Table of Contents

- Preventive vs Urgent Care

- Employers Believe Employees Are Primarily Responsible for Their Own Wellness

- What Employers Mostly Do and What Actually Makes the Most Difference Are Two Different Things

- The relationship between work friction and wellness

- Minimize Work Friction or Maximize the Wellness Program

Are Wellness Programs Really a Preventive Measure?

A summary of the details of the article will go here.

The data on wellness programs tell a pretty confusing story. On one hand, the percentage of companies that have them has hovered around 40%–60% for nearly a decade [1]. The CDC appears to be a fan of them, and there’s certainly no shortage of websites that will tell you your organization needs one. (We don’t necessarily disagree; see below.) There’s some evidence that the best programs have good ROI (typically measured in terms of a firm’s healthcare costs), which wellness program providers are naturally turning into major profits: Between now and 2030, the US corporate wellness market’s CAGR is forecast at 4.47%; by 2028, the global market is expected to do even better with 8.2%.

On the other hand, if you look closely at the last decade of data, organizations don’t seem completely convinced of the value of these programs. The percentage of SHRM members reporting they offer one has fallen (not in a straight line) from a high of 59% in 2019 to 44% in 2023. The best study of these programs, contracted by three US government agencies and conducted by RAND in 2012 (old, we know, but it really is the best), may help explain why. That study concluded:

- Employee participation is usually low (20%-40% of those eligible)

- Most employees who do participate are the ones who’re already healthy.

- Incentives boost participation “only modestly”

- Whereas the ROI of disease management programs (in which only 13% of eligible employees participated) was probably worth it ($3.80 saved on healthcare costs for every $1.00 spent on the program), lifestyle management programs (in which 87% of eligible employees participated) actually lost companies money ($0.50 for every $1.00 spent)

In 2019, the KFF drew a similar conclusion in another unusually large and thorough study: “Despite the prevalence of workplace wellness programs, numerous studies find limited evidence of their effectiveness in promoting health or preventing disease.”

Preventive vs Urgent Care

That might seem weird, because SHRM defines wellness programs as benefits that “are provided to employees as a preventive measure to help avoid illness while improving and maintaining the general health of employees”[2]. For sure, that’s the intent. But whether it’s free health screenings, chronic disease management, smoking cessation assistance, weight loss coaching, discounted gym memberships, healthy snacks, onsite yoga, mental health support, or any of the other dozens of things wellness programs can include, FOUNT sees these programs more like an emergency room than true preventive care.

We suspect organizations secretly feel the same, so in 2022, when our friends at Executive Networks asked us to design a small survey for an upcoming event of theirs on employee wellness, we wanted to know:

- How much responsibility do organizations really feel for employee wellness?

- What do they think they can do to make a meaningful difference?

- What do they hope to get out of wellness programs?

We knew the answer to the third question already: reduced healthcare costs and absenteeism, improved labor productivity and candidate attraction, and to be perfectly honest, just a good old-fashioned feeling that they’re doing the right thing. So, we didn’t ask that question. But we did circle around the other two. Here’s what 75 HR leaders said.

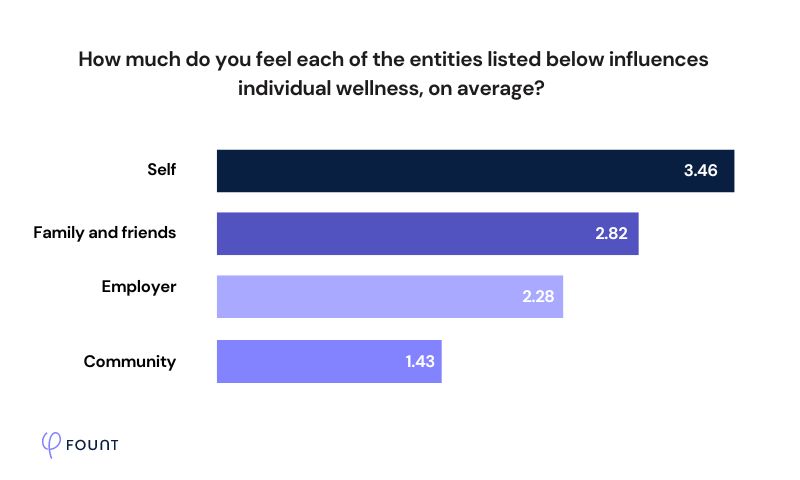

Employers Believe Employees Are Primarily Responsible for Their Own Wellness

When we asked respondents to rank the influence of four parties on individual wellness, 66% put “Self” at the top. “Employer” most often came in third, after “Family and friends” but before “Community”.

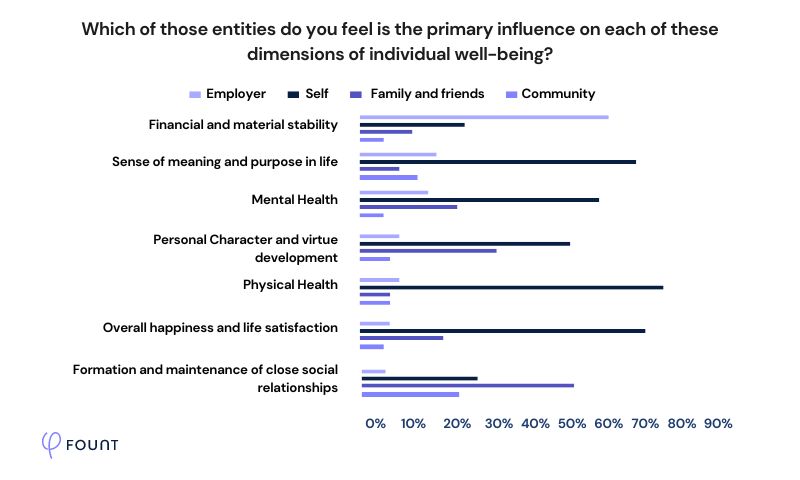

When we broke out kinds of wellness (mental, physical, etc.), the only kind on which respondents said employers have more influence than the individual themselves was “Financial and material stability”.

And when we drilled down to find out roughly how much influence respondents believe employers have on these kinds of wellness, 69% again said “A great deal” for “Financial and material stability”; 32% said “A great deal” for “Mental health”; and 23% said “A great deal” for “Sense of meaning and purpose in life”. Fewer than 20% of respondents said “A great deal” for all the other types of wellness.

In short, these respondents’ answer to the question, “How much responsibility do organizations really feel for employee wellness?” is pretty clear: Not much—at least not relative to what they think is employees’ own responsibility, with the sole exception of financial stability.

What Employers Mostly Do and What Actually Makes the Most Difference Are Two Different Things

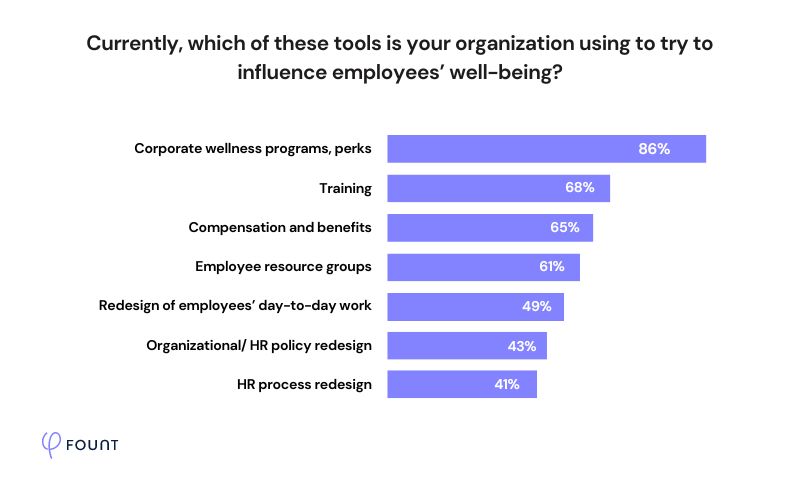

Despite believing that their organizations don’t have much influence on individual wellness, only 1% of respondents said they’re not doing anything to try to improve it. The most popular tool among the other 99% was, of course, corporate wellness programs [3].

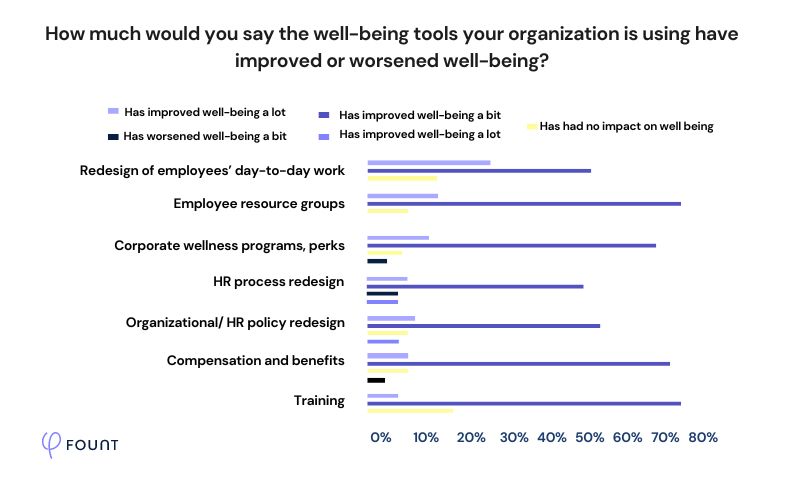

But when it comes to what’s actually improving employee wellness, the stand-out tool isn’t corporate wellness programs. Sure, nearly 70% of respondents said these programs have “improved well-being a bit”, but less than 15% said they’ve “improved well-being a lot”. The biggest difference-maker, it seems, is “redesign of employees’ day-to-day work”—which less than half of respondents are doing.

In other words, we know what we need to do to actually improve employee wellness: Design work that doesn’t make them unwell in the first place. But… most of us are still just offering a band-aid once the damage has been done.

The relationship between work friction and wellness

I wish I could tell you we’ve got hard numbers linking work friction and wellness, but we don’t (yet). What we do have is hundreds of employees telling us about work friction they experience in terms that pretty clearly suggest their wellness is being impacted by it. Here are just a dozen examples from our August 2023 survey of 506 employees.

Financial and material stability

“Give my best and all daily but no raise of any kind for 10 years or so. Isn’t 10 or so years long enough?”

“I was told I would be refunded for my diesel for traveling to work and then wasn’t approved when I requested reimbursement.”

“The policy has gone from working two days in-office a week to now three days, and parking is $20 a day and not covered by the company. I have to spend more time commuting to work and more money on gas and parking.”

“The policy has gone from working two days in-office a week to now three days, and parking is $20 a day and not covered by the company. I have to spend more time commuting to work and more money on gas and parking.”

Mental Health

“Ladies in the office were constantly trying to put the blame on the new person. I would go home and cry. I was suicidal.”

“The constant no-matter-how-much-I-do-it’s-not-enough. It leaves me feeling like I am giving it my all and don’t know what else to do. Gives me the ‘why try?’ thoughts.”

“When my personal morals are compromised and customer service suffers, I feel extremely unhappy and stressed in my work, thus impacting my job performance and my health.”

Physical Health

“Employees are getting hurt on the job.”

“Have to work more hours when my coworkers are sick even if I am sick.”

“I work in an outside environment and there’s barely enough fans to keep our growing staff cooled down in the heat.”

Formation and maintenance of close social relationships

“Not possible to take vacations at the right moment with my family.”

“Employees are being discriminated against for being a parent.”

“Holidays from work are only approved closer to the time which causes frustration at being unable to plan long-term.”

Clearly, these employees’ wellness is suffering because of work friction. Bad policies, bad processes, bad equipment, and bad relationships take their toll on employees’ mental, physical, and financial health. And according to the UK’s Health Foundation, the more “low-quality work factors”—all of which are sources of work friction in our survey data—people experience, and the longer they experience them, “the more likely they are to have worse health”. In 2020, the Foundation found over a third of UK employees were in low-quality work, and those individuals were more than twice as likely as people in high-quality work to report poor health.

Minimize Work Friction or Maximize the Wellness Program

If you’ve been paying attention, you know this question presents a false dichotomy:

Work friction reduction is itself a critical component of any effective wellness program.

In medicine, both preventive and urgent care have their place, and we believe the same is true in places of employment. Above, we’ve seen how employers actually influence employee health—and how they don’t. On the basis of that evidence, we suggest you flip the scales of your investment in these two types of care by taking the following steps:

- Re-assess the value of your urgent care programs.

- Break the full program down into individual components (chronic disease management, lifestyle management, health coaching, etc.).

- Measure each component’s value. It’s relatively easy to measure eligible employee participation, impact on absenteeism, and savings on healthcare costs; it’s harder to measure impact on labor productivity and candidate attraction, but at least try.

- Cut program components that aren’t worth what you’re paying for them.

- Introduce and prioritize truly preventive care.

- Reinvest the funds from cut urgent care programs into truly preventive wellness measures, like reducing work friction for employees.

- Use surveys, interviews, and other listening tools to identify where work friction happens in your organization, how bad it is, and what causes it.

- As you begin to target sites of work friction for intervention, you’ll have a sense for which ones are probably impacting wellness the most—but don’t just trust your gut. Develop measures of wellness directly tied to each type of work friction so you’ll be able to both invest your money wisely and prove your investments paid off.

REFERENCES:

Related Resources

See all News

FOUNT News

LIVE Webinar. Beyond AI Hype: How to De-Risk Your GBS Transformation with Friction Data

Guest Post

3 Signs Your GBS Is Creating Friction Instead of Flow (And How to Fix It)

FOUNT News

June Newsletter: Friction is Killing Your AI ROI.

Insights

Breaking the False Tradeoff in GBS: Efficiency vs. Experience

Events

LIVE Webinar – July 9th for SSON Network. Beyond AI Hype: How to De-Risk Your GBS Transformation with Friction Data

Insights

To Create New Value, GBS Leaders Need Different Data

Insights

How to Keep Up with the Latest AI Developments

Insights

APRIL Newsletter. Friction: You Can’t Improve What You Can’t See